🌀Scrum: The Agile Trap That Keeps on Sprinting

🌀 Table of Contents

- Introduction

- 🎯 When Velocity Becomes the Target

- 🧬 When Complexity Compounds

- 🏗️ When the Framework Doesn’t Fit

- 🤔 Expectation vs. Reality

- 🏁 Conclusion

- 📚 References & Further Reading

Introduction

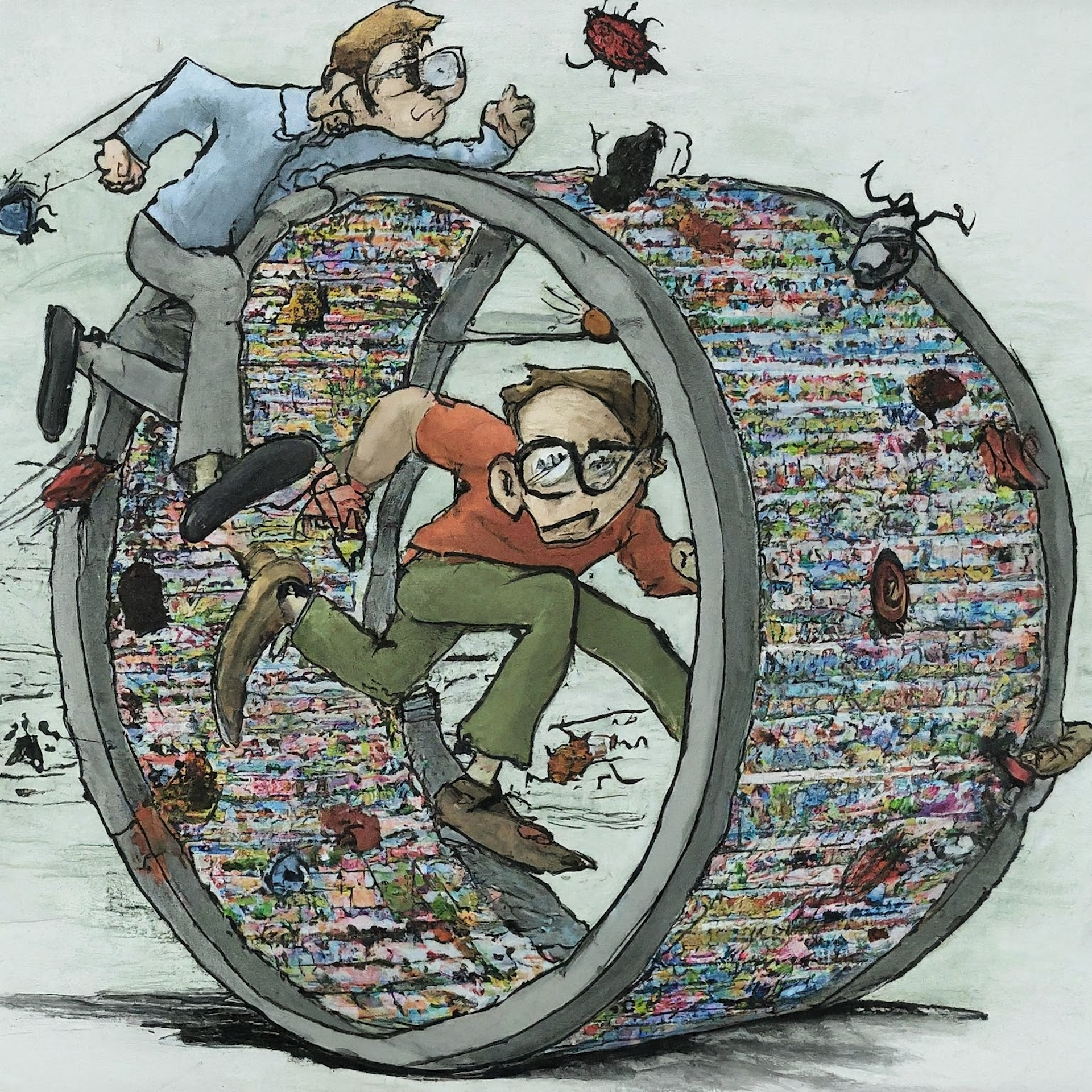

Welcome, fellow practitioners of the software arts. 🤓 What follows is a rigorous examination of Scrum—that beloved framework which has achieved near-liturgical status in our industry. We shall dissect its failure modes with academic precision, gallows humor, and the weary wisdom of someone who has mass-updated Jira tickets at 4:47 PM on a Friday. Prepare your retrospective sticky notes; today we question the unquestionable.

Scrum has achieved near-religious status in Agile software development, adopted almost reflexively by teams across the industry. But beneath its polished ceremonies lies a methodology that can do more harm than good. Let’s examine the pitfalls of Scrum and why it might be time to reconsider.

“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” — commonly attributed to Einstein, though actually a paraphrase of his 1933 Oxford lecture1. And yet, frequently ignored during sprint planning.

🎯 When Velocity Becomes the Target

🤓 Nerdy Aside: These dysfunction patterns have a name—Goodhart’s Law. As Marilyn Strathern generalized it: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”2 The moment velocity becomes the metric by which teams are judged, velocity becomes what teams optimize for—not value, not quality, not problems solved. The map eats the territory.

🏚️ The Ever-Lowering Bar

In an effort to meet Scrum’s lofty goals, teams often find themselves setting the bar lower and lower with each sprint. Before you know it, you’re celebrating the completion of tasks like “update the README file” and “fix a typo in the comments.” Talk about aiming high!

🧭 The Ticket Selection Dance

As a sprint progresses, developers start eyeing tickets they think can be finished before the sprint ends, rather than tackling the most important tasks. It’s like choosing to do the dishes instead of studying for a final exam—sure, it feels productive, but is it the best use of your time?

Lean practitioners call this local optimization—optimizing for the sprint metric at the expense of system-wide value.3 The incentive structure is clear: finishing a small ticket feels good and “counts.” Starting an important but uncertain ticket risks rollover. Rational actors respond to incentives. The sprint boundary is the incentive.

🧬 When Complexity Compounds

🔥 The Entropy Tax

Here’s a pattern I’ve observed repeatedly: a significant portion of sprint work traces back to fixing bugs from earlier tickets. Feature A ships in Sprint 3. Sprint 5 brings “Fix edge case in Feature A.” Sprint 7 delivers “Refactor Feature A for performance.” Sprint 9? “Address security vulnerability introduced by Feature A refactor.”

This is the entropy tax—the inevitable cost of adding features to a codebase with increasing complexity. Scrum’s sprint structure obscures this by treating each ticket as independent, when they’re actually nodes in a dependency graph that only grows more tangled. The velocity chart says 40 points per sprint. The codebase knows the truth.

🔄 Backlog Purgatory

Unfinished tickets get ceremoniously moved to the next sprint, creating a never-ending cycle of rollover. It’s like Groundhog Day, but instead of Bill Murray, it’s exhausted developers wondering if they’ll ever see the light at the end of the backlog.

The backlog becomes a graveyard of good intentions. Every retrospective adds more tickets. Nothing ever leaves. Practitioners observe that 30-70% of backlog items are never implemented.4 These “zombie tickets” shamble along indefinitely: too politically sensitive to delete, too stale to prioritize. It’s thermodynamically inevitable.

🏗️ When the Framework Doesn’t Fit

🚦 The CI/CD Paradox

The tension between Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment and sprint boundaries raises a perplexing question: Why use sprints if we’ve implemented CI/CD? CI/CD encourages frequent, incremental updates to deliver value quickly. Sprints create artificial barriers that hinder this continuous flow.

If you’re deploying 10 times a day, what exactly is the sprint boundary measuring? It’s like putting mile markers on a river.

While Scrum was introduced at OOPSLA in 1995, the first official Scrum Guide wasn’t published until 20105—before widespread cloud adoption and modern CI/CD pipelines. The two-week batch made sense when deployments were expensive. That constraint no longer exists. We’ve kept the ceremony while losing the rationale.

🔬 The Micromanaging Scrum Master

And let’s not forget the well-meaning but often overbearing Scrum Master who turns daily stand-ups into interrogation sessions, demanding detailed explanations for every minute spent. Because nothing screams “agile” like justifying your bathroom breaks.

The problem isn’t necessarily bad Scrum Masters—it’s a role definition that conflates facilitation, coaching, and accountability in ways that invite dysfunction. When “servant leadership” lacks clear boundaries, it devolves into status reporting with extra steps.

🤔 Expectation vs. Reality

| Expectation | Reality | |

|---|---|---|

| Delivery | 📦 Predictable releases | 📋 Predictable meetings |

| Priority | 📍 Focus on highest-value work | 🧹 Focus on what fits in the sprint |

| Improvement | 🌱 Continuous growth | 🔄 Continuous rollover |

| Autonomy | 🧩 Self-organizing teams | 🔬 Daily status interrogations |

| Responsiveness | 🌬️ Agility to shifting winds | 🧊 Two-week batching cycles |

| Completion | ✅ Done means done | 🏚️ Done means “moved to next sprint” |

| Planning | 🧠 Right-sized work conversations | 🎰 Estimation poker theater |

| Metrics | 📊 Actionable flow data | 🏃 Velocity as vanity metric |

🏁 Conclusion

“Tell me how you measure me, and I will tell you how I will behave.” — Eliyahu M. Goldratt, The Haystack Syndrome6

While Scrum has its merits, it’s important to recognize its potential drawbacks. From lowering the bar to micromanagement, Scrum can do more harm than good. The research backs this up: the DORA metrics that actually predict software delivery performance—deployment frequency, lead time, change failure rate, and recovery time—have nothing to do with velocity.7

So, the next time someone suggests implementing Scrum, consider if it’s really the best fit—or if it’s just another process trap in agile clothing. 🪤 If this resonates, try Kanban, Shape Up, or simply… fewer meetings. Your team’s actual output will tell you if it’s working.

Scrum isn’t evil—it’s a tool. But tools have affordances, and Scrum’s affordances push teams toward ceremony over delivery. Choose deliberately.

Class dismissed. There will be no retro. 🤓

⚖️ Fair Warning: I’ve seen wonderful project managers working as Scrum Masters who weren’t overbearing micromanagers. I’ve also seen good Scrum teams adjust their process and actually work in an agile fashion, delivering good software on time. However, I’ve seen the situation described in this article much more often. My personal preference is an actually agile Kanban process, modified for the engineering team and the type of software being built. 🌊

📚 References & Further Reading

Foundational Texts

- Beck, K. et al. (2001). Manifesto for Agile Software Development. The original principles—notably silent on sprints, points, and ceremonies.

- Schwaber, K. & Sutherland, J. (2020). The Scrum Guide. The official framework—worth reading to see how far implementations have drifted.

Critiques & Alternatives

- Anderson, D. J. (2010). Kanban: Successful Evolutionary Change for Your Technology Business. Blue Hole Press. The foundational text on flow-based development.

- Jeffries, R. (2018). Developers Should Abandon Agile. One of Agile’s original signatories calls out what it’s become.

On Measurement & Performance

- Forsgren, N., Humble, J., & Kim, G. (2018). Accelerate: The Science of Lean Software and DevOps. IT Revolution Press. Research showing what actually drives performance (hint: not sprint velocity).

- Goldratt, E. M. (1990). The Haystack Syndrome: Sifting Information Out of the Data Ocean. North River Press. Source of the measurement quote—and essential reading on metrics dysfunction.

Footnotes

-

Einstein’s actual words, from his 1933 Herbert Spencer Lecture at Oxford: “The supreme goal of all theory is to make the irreducible basic elements as simple and as few as possible without having to surrender the adequate representation of a single datum of experience.” The pithy paraphrase appeared decades later. ↩

-

Strathern, M. (1997). “‘Improving ratings’: audit in the British University system.” European Review, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 305-321. This is the popular generalization of Goodhart’s original 1975 formulation. ↩

-

See Reinertsen, D. G. (2009). The Principles of Product Development Flow. Celeritas Publishing. Chapter 3 covers local vs. global optimization in detail. ↩

-

This is practitioner observation rather than peer-reviewed research—a notable gap in the literature. The phenomenon of “backlog bankruptcy” (periodically deleting stale items) is widely recognized but understudied. ↩

-

Scrum was introduced at OOPSLA 1995, but the formal Scrum Guide document was first published in 2010 and has been updated in 2011, 2013, 2016, 2017, and 2020. ↩

-

Goldratt, E. M. (1990). The Haystack Syndrome, p. 26. Often misattributed to his more famous The Goal (1984). ↩

-

Forsgren et al.’s research, based on 23,000+ survey responses, found high performers deploy 200x more frequently with 106x faster lead times. Velocity was explicitly identified as an invalid productivity metric. ↩